SMART NFRs, SMART Teams

Applying System Design to Engineering Management

toString() delivers no-fluff, deep dives on practical AI & software engineering—hit “Subscribe” to get each new post in your inbox.

I was recently talking with another Engineering Manager friend of mine about one of the most crucial aspects of our role: setting the right expectations with our teams. We both agreed that clear expectations are instrumental in enabling both individual contributors and teams to achieve high performance. But more importantly, they make those dreaded "difficult conversations" practically disappear, when everyone understands what success looks like, there are rarely any surprises.

But then came the key question: How do you actually set expectations the right way?

As engineers-turned-managers, we often struggle with this transition from concrete technical problems to the seemingly abstract world of people management. That's when I realized something: I already had a proven framework for this.

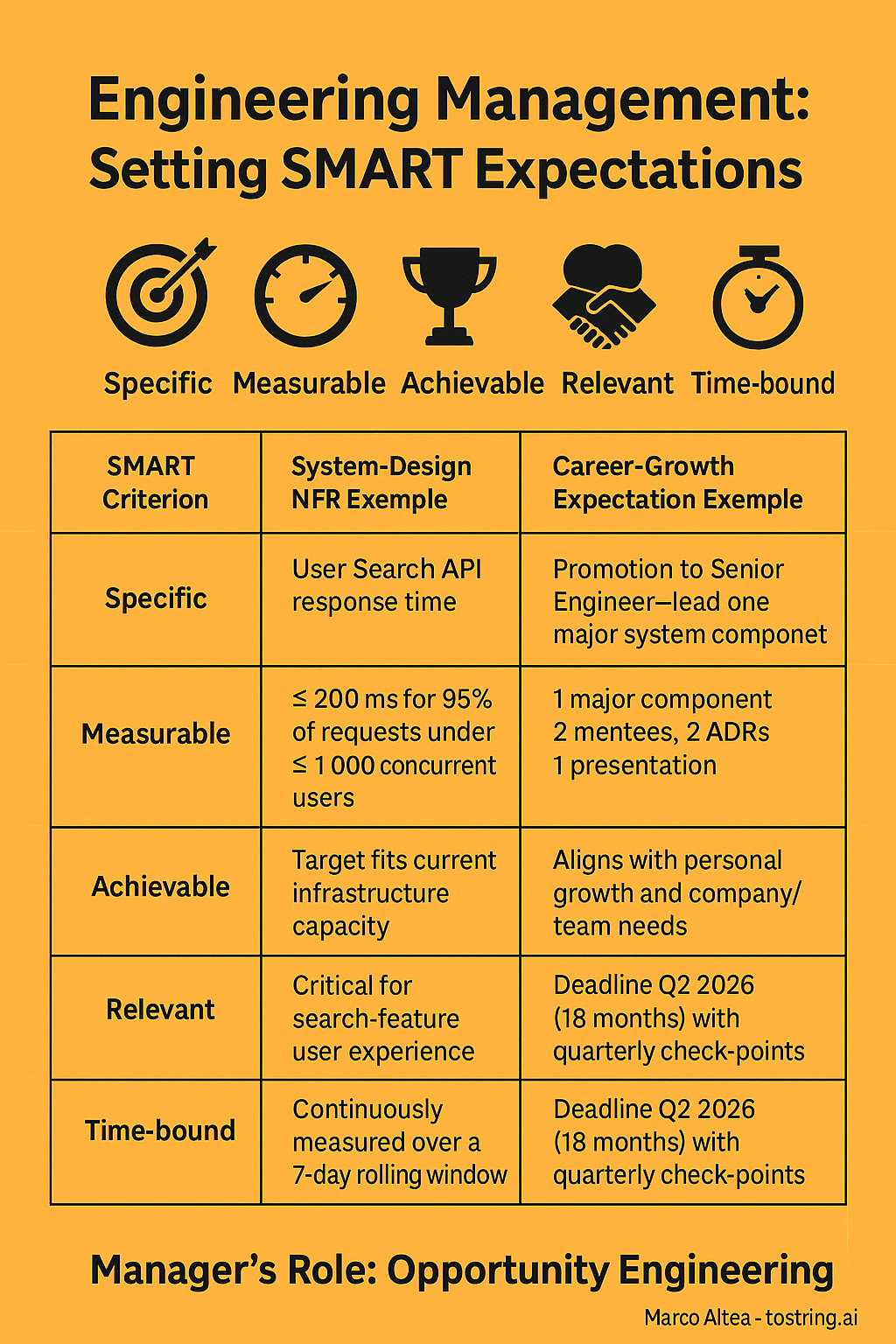

I treat setting expectations exactly like defining Non-Functional Requirements (NFRs) during system design—using the SMART method.

When I define NFRs for a system, each requirement must meet all five SMART criteria. The same principle applies to team expectations. Let me show you what this looks like in practice.

Instead of: "The system should be fast"

SMART NFR: "The user search API must return results within 200ms for 95% of requests under normal load (up to 1000 concurrent users) during business hours, measured over a 7-day rolling window."

Let's break this down:

Specific: User search API response time

Measurable: 200ms response time, 95% of requests

Achievable: Realistic target based on current infrastructure

Relevant: Critical for user experience in search functionality

Time-bound: Measured continuously with 7-day rolling assessment

In my opinion, this approach and mindset match the one needed when creating and setting expectation with your team members, let me give you an example

Instead of: "You should grow technically and aim for the next level"

SMART Career Expectation: "To reach Senior Engineer level within 18 months, lead the design and implementation of one major system component (affecting 3+ services), mentor two junior developers through their onboarding and first projects, contribute to architectural decision records (ADRs) for at least 2 cross-team initiatives, and present one technical deep-dive to the engineering all-hands by Q2 2026."

Breaking this down:

Specific: Senior Engineer promotion with defined leadership activities

Measurable: 1 major system component, 2 mentees, 2 ADR contributions, 1 presentation

Achievable: 18-month timeline with incremental milestones

Relevant: Aligns with both individual growth and team/company needs

Time-bound: Clear 18-month deadline with quarterly checkpoint (Q2 2026 presentation)

This example shows how you can apply SMART methodology to:

Technical growth (system design leadership)

People skills (mentoring)

Organizational impact (cross-team collaboration)

Communication (technical presentations)

The beauty is that both me and the engineer know exactly what "success" looks like, making performance reviews and career conversations much more objective and productive. No surprises, no ambiguity.

But wait—why do we even need managers in the first place? Can't AI handle this?

It's a fair question, especially as AI becomes more sophisticated at analysing performance data, generating feedback, and even conducting initial performance reviews. AI can certainly identify patterns in code quality, track delivery metrics, and flag potential issues faster than any human manager.

However, there's something uniquely human about the role that goes beyond pattern recognition and data analysis. Management isn't just about monitoring performance— it's about creating the conditions for people to succeed.

Defining SMART expectations is only half the equation. As an engineering manager, you can't just set these clear goals and then hope your team member magically finds the opportunities to achieve them.

You need to actively architect the environment for success - just like how you'd provision the right infrastructure to meet your NFRs.

The Manager's Role: Opportunity Engineering

Going back to our career goal example, let's see what this means in practice:

If the expectation is: "Lead the design of one major system component affecting 3+ services"

My job as EM is to:

Identify upcoming projects that naturally involve cross-service architecture

Advocate upward to ensure your engineer is considered for the technical lead role

Shield them from competing priorities during the design phase

Connect them with stakeholders from the affected services early in the process

Provide air cover when they need to make architectural decisions that might slow down initial development

If the expectation is: "Mentor two junior developers"

My job as EM is to:

Time new hire onboarding so they can be the primary mentor

Structure work allocation to pair them with junior team members on meaningful projects

Help them create mentoring frameworks (1:1 templates, goal-setting processes)

Recognize their mentoring efforts publicly in team meetings and performance reviews

Give them budget/time for mentoring activities without penalizing delivery metrics

The Infrastructure Analogy

Think of it like system design: you wouldn't define an NFR for 200ms response time and then deploy on a single overloaded server. Similarly, you can't expect career growth without creating the right "infrastructure":

Resource allocation (time, budget, tools)

Network effects (introductions, cross-team relationships)

Reduced friction (removing blockers, providing context)

Monitoring and feedback loops (regular check-ins, course corrections)

The difference between good and great engineering managers is that great ones actively engineer these opportunities, rather than waiting for them to emerge naturally.

From Requirements to Results

Just as we wouldn't ship a system without proper NFRs, we shouldn't manage teams without SMART expectations. But the real magic happens when you combine clear requirements with intentional opportunity engineering.

The next time you're frustrated with a team member's performance, ask yourself: Have I defined success as clearly as I would define a system requirement? And more importantly, have I architected the right conditions for them to meet that success?

Your role as an engineering manager isn't to be a human performance monitoring system—that's what dashboards are for. Your role is to be the infrastructure architect for human potential.

The best systems are designed with both clear requirements and the right infrastructure to meet them. The same principle applies to building high-performing engineering teams.

So go ahead, treat your next 1:1 like a system design session. Define the requirements, architect the opportunities, and watch your team deliver exactly what you specified—because that's what good engineering is all about.

What's your experience with setting clear expectations? Have you found other software engineering principles that translate well to people management? I'd love to hear your thoughts in the comments below.

Working with cross-functional teams, I have seen how easy it is for non-functional requirements to get sidelined until they cause real problems. Calling them “smart” only matters if they are treated as part of core planning, not an afterthought.

What a time, you are inspiring every day. Well said, thanks for sharing it.